Lccorp2 went to work sporking Bitterwood, The Pearls, and Hawkmistress!. He also wrote a few writing-related articles.

Articles by lccorp2:

Sounds a little strange, isn’t it? Still, some of you who’ve been watching my LJ may remember that little post I made some time ago about letting your readers do your describing for you. Since I’m a little tired of Bitterwood (and my brain needs a little time to recover) I thought I’d expound a little on the concepts I pointed out therein.

You’ve probably been told by whoever it is that inducted you into writing to “show, don’t tell”. While this, like all other “rules” of writing, is more of a guideline than anything else (since it’s like drawing. If you can make it look good, it doesn’t matter what you do), it’s still there for a reason, and it’s a very good reason indeed—enough for it to hold most of the time. Showing tends to grant better immersion and character empathy for the reader, and tends to be more involved and open-ended (within the limits set by the prose) for the reader’s imagination to take over. Still, this isn’t a showing vs. telling discussion, and I’m not going to let it be one, so there.

So far, I’ve encountered while both reading and writing four ways of getting across information to the reader that will help fill in and colour the details of your characters to the reader. This list probably isn’t exhaustive—I’m not going to claim that—but it does cover the more common ways of getting description across. Some methods may combine one or more of the following, and it’s important to know when to use what to maximum effect.

Note that these are my personal terms for these methods, and are by no means “official” or anything on those lines.

1. Infodumping

2. Breaking up and hiding

3. Direct inference

4. Imaginative inference

Infodumping

Infodumping’s probably the most common method that authors use in speculative fiction on order to get across how something looks, smells, tastes, feels, and sounds, although the most commonly appealed-to sense is of course, sight. This may have had its roots in that humans are primarily very visual creatures, but most writers are indeed aware that good description (for a relative value of good) should appeal to all the five senses and at least try to cater to sound, and perhaps smell. Infodumping depends highly on “telling”—directly stating how something is, and I believe that such things work for “neutral” statements—things like a character’s height, eye colour, the fact that the lilies are blooming, that the cloud in the sky looks like a bird, so on and so forth. “Loaded” statements—things which I’m suppose to judge the characters on, especially on moral attributes such as kindness, valour, honesty—are better off shown and left to the reader’s imagination, and this post isn’t on them anyways.

The main problem of infodumping, of course, is that it brings the flow of the plot and prose to a screeching halt, stopping all action while the author takes utter care in describing the wonderful rustic countryside, the incoming new character from a foreign land, or perhaps the new bustling city. Everyone else takes a break while the Wise Old Mentor carefully explains to the Young Dunderheaded Hero about the Scepter of the Seven Seas or the Ruby of Rude Rowdiness of what-have-you, and the reader’s eyes glaze over, because frankly, he or she couldn’t give a damn because you, as the author,didn’t give them reason to.

It’s also very hard to do anything else other that flat out information-relaying with an infodump, since these by definition are huge blocks of exposition—often written in third-person-omniscient, to make the problem worse.

True enough, sometimes it’s impossible to avoid an infodump. Perhaps one must know why werewolves are bad, or why the violet-eyed men of the sea are impervious to all edged weapons. Perhaps the description of the countryside will figure into the chase scene across said countryside in the next chapter, or maybe the heroine will take the string of beads off that traditional dress shop and use them as a makeshift garrote. Still, it’s imperative that the infodump be kept as short as possible, and as always, the author should try to split it up if possible and stuff it discreetly into the prose (which is point two.)

Infodumping isn’t completely bad—it does have its virtues in that it’s direct, to the point, and there’s no chance of misinterpretation or ambiguity. The problem is that these virtues are as equally mirrored by the method in point two, breaking up and hiding, and I personally feel point two does a better job of direct telling without the cons of infodumping. However, if you’re willing to take the hit because it is so essential that your character has violet eyes, that they play such an important role in the plot that you’re afraid the reader will miss this detail and want to draw all the attention you want to it—fine. Just please, make sure you’ve given your readers a reason to care about the character, or they’ll just skim over the description and not notice that yes, your character has violet eyes.

Breaking up and hiding

Breaking up and hiding is also very commonly used by authors in the genre, and is what it says on the label—the pertinent exposition is broken up into chunks and scattered across the prose. The degree, scope, and forms of breaking up and hiding are very wide and diverse; for example, it may be hidden in a dialogue tag:

“Blah blah blah,” she said, toying with her golden hair.

The above is a rather obtrusive example, but still much better than the traditional infodump. Dialogue is also used to hide exposition:

“And he ran all the way here like an Ankaran mare!”

“Really?”

“Yes! That fast!”

From here, we can see that an Ankaran mare is supposed to move fast, and the fact is disguised in a simile that’s being said in dialogue. This one’s better-disguised than the previous example, but of course, circumstances dictate all—if the character in question is not used to fidgeting or using similes in speech, there’s going to be a bit of incongruity and the disguise is going to be lost.

Still, I personally favour this method for getting across information that needs to be explicitly stated, like how Victor has an underbite or how the spaghetti monsters from the planet Zog have three nostrils. Done right, it can blend seamlessly and naturally into the prose, and yet retain all of the clarity and directness which infodumping has. It’s also much easier to do more than one thing with breaking up and hiding (naturally, since you’re trying to hide the exposition in something else):

Victor beamed. “She’s got her daddy’s underbite.”

This snippet does two things: firstly, it establishes a physical attribute of two characters, and implies how one of them feels about this. Of course, knowing further that this is Victor talking about his daughter, it further implies more things about their relationship, about how Victor feels about physical resemblance between family members, how underbites are viewed, and more, if you’re willing to give it a bit of a stretch. Try to imagine how I’d have done this in a traditional infodump. Hard, isn’t it?

Direct inference

Now we’re moving into showing territory. Direct inference usually comes from a character’s actions, and while it’s the primary way of showing “loaded” attributes, I’ve already stated I’m not going to go there. The difference between direct inference and hiding is that nowhere is it stated that character A has X physical attribute. An example would be a character having to duck under a doorway (of course, this wouldn’t apply in, say, a human entering a hobbit’s home). Nowhere is it mentioned that the character is tall, but the reader can infer that the character is tall—otherwise, why would he need to duck under the doorway in order to enter?

Of course, this can be a problem if what’s inferred clashes with any preconceived notions about the character the reader has brought in, or god forbid, your own explicit description. You’ve heard me complain recently about how Metron using a cane in Bitterwood was absolutely jarring, because the inference (biped) clashed with the preconceived notion of standard fantasy dragons (quadruped) and that there was no hint or suggestion prior to that scene that it wasn’t the case. Although to be fair, this isn’t the fault of the method itself—there simply wasn’t enough setup prior to the scene, and if it’d been mentioned there and then that been biped I would have been thrown out of the prose as well. (Although probably not as violently)

Another potential problem with direct inference is that thanks to our good old social theory of symbolic interactionism, what you intend the reader to infer from a certain action, possession, or whatnot may have a very different effect from what you intended. To take some “loaded” examples, since they’re more common, you’re all familiar with Paolini and his hippie vegan atheist elves, and how he meant them to be superior to everyone else. We know better; it just makes them look stupid, deluded and pretentious. Of course, this is an extreme case. You’re also familiar with Twilight and how Edward stalking Bella is supposed to be reflective of his love for her, but to us it just makes him appear creepy and obsessed.

Now let’s try to translate this to physical attributes. Someone who eats slowly might be neat, or he might have a weak jaw, or cavities, or be in the mind to enjoy his meal, or might not have a very wide mouth, or…you get the idea. It’s probably good in such ambiguous situations to back up direct inference with a little breaking up and hiding of telling to get rid of ambiguity—unless that’s what you’re aiming for.

Imaginative inference

This is where the deliciousness sets in. Imaginative inference, as I see it, is where there is near-to-none description of the characters in question and the reader is guided by the author in constructing his or her own personalised vision of the characters through said characters’ actions, dialogue, thoughts, and so forth. Since it’s often part of the reader’s imagination, imaginative inference in action is often hard to spot, but a very good example of this would be Jo Walton’s Tooth and Claw—a parody of the Victorian Novel. Save for the most important traits, the characters are almost never described, and the author guides the reader through the use of tropes of the Victorian Novel to establish settings, characters, and backgrounds.

In short, it’s a big game of “let your imagination and knowledge fill in the blanks”.

The advantages are obvious—there’s no jarring or breaking of the action to speak of, since there’s no explicit description at all. The reader is actively engaged in the process of forming the characters, and there’s not much reason to be bored. A bit of shameless plugging here, but I’ll just include a small snippet from the beginning of Morally Ambiguous to illustrate my point:

Nodammo had dropped the first sugar cube in her tea when the hero alarm went off.

“And we haven’t even opened for the day,” she said before she stirred in another sugar cube and watched it dissolve, ignoring the bells that rang throughout the tower. “Agnurlin, would you be so kind as to check whether the village children have been playing with the heroism detectors again? I’ve had it with the false alarms.”

“Will Mistress be wanting the usual this morning?” A rather tall and yellowed skeleton stood by the dining table, and with a practiced half-bow set down a tea-tray and a platter of honey-lined fruit sandwiches. Nodammo wondered once again how her butler managed to keep his waistcoat starched and spotless, then reminded herself she had more important things at hand.

“Yes, thank you. Agnurlin, would you mind hurrying up? Can’t be too careful with heroes turning up around these parts of late.”

“My apologies, Mistress.” Agnurlin crossed the dining hall to the wide balcony in a very butler-like gait, the tap-tapping of his feet on the masonry creating echoes in the dining hall’s corners. Once he was out of sight, Nodammo made short work of her tea and considered consequences. The last three alarms had been duds, two of them caused by straying children and another by a flying cow, but it never hurt to be vigilant.

After all, it’d been complacency that’d killed her grandfather.

“What do you think the hero alarm means, Victor?” she asked between sips of her tea. “Has the Company finally started making inroads here?”

The black dragon curled by the enormous fireplace stirred; one draconic eye opened, fixed itself on Nodammo, and shut again. “I hate hero alarms, especially when they go off during breakfast.”

“You hate everything, Victor!”

“Too much noise, Boss. Couldn’t you at least set them to play some soothing music instead of this din? Greendowald’s Fifth Symphony might be a good choice.”

“Victor…”

The black dragon reached out, speared a sandwich on a claw tip and dropped it daintily on his tongue. “Just make it stop. I hate the way it drones on.”

“Fine.” Nodammo waved a hand, and the deafening ringing stopped. “Better now?”

“Very much so. We’ve a long day ahead; no point starting it in a downdraft. Now would you be so kind as to hand over the lemon crackers? Not very filling, but that’s biscuits for you.”

Between sorceress and dragon, the lemon crackers and fruit sandwiches steadily disappeared till only crumbs remained.

“What’s taking Agnurlin so l—eeyagh!” A stray strawberry slice bounced off the front of Nodammo’s dress and landed on the floor. “Agnurlin, I am not my mother! I know she hasn’t been in retirement for that long, but please don’t do that!”

Agnurlin contrived to look innocent, despite having no facial muscles, and pulled a spyglass out from his waistcoat. “Mistress, you might want to see this. Heroic activity has been detected in the direction of the Generic Little Village.”

“You mean the one with a capital ‘G’, ‘L’ and ‘V’?”

“The very one, Mistress.”

“Well, no point in dragging the matter out. The best hero is one where you’ve cleared up the bloodstains before lunch.” Without another word, Nodammo took the spyglass from Agnurlin, strode out on the balcony, and put the spyglass to her eye.

“Oh,” she said at last. “Botheration.”

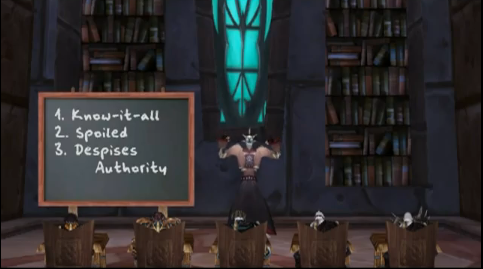

What do you think Nodammo looks like? What would someone who had a butler, listened to classical music, drank tea from teacups and have small fruit sandwiches and lemon crackers, so on and so forth look like? Here I’m trying to draw on the “cultured” stereotype that many people are aware of, and by having Nodammo act in such a manner and people recognize the stereotype, they immediately draw up the image of such a person associated with the stereotype. It seems to have worked; most of my beta readers, after having gone through a few chapters, reported they got the impression of Nodammo as a strict, English-esque young lady.

For a lark, let’s take Victor out for a two-snippet spin:

“I hate little villages.”

“Now, there’s no need to keep up appearances here, Victor,” Agnurlin shouted over the shrieking wind. “We’re going into the village to get some white lettuce, check whether the hero has arrived yet, and that’s it. Why don’t you land in that grassy patch over there?”

“I hate white lettuce.”

“But white lettuce is good for you. Mistress says it’s very cleansing for one’s insides, even for dragons. Cooked in soup, the nutritive and alchemical value increases—”

“I hate soup.”

***

Nodammo hadn’t remembered Victor’s teeth being so sharp.

“Boss, I understand what you’re getting at and you have my interests in mind, but please, please don’t ever fucking pull rank on me again, because I HATE PEOPLE PULLING RANK ON ME. I call you ‘Boss’. That means I’m an employee, and that entails the happy fact that I can quit any time I like if you start treating me like a goddamn pet. It’s all there in your granddaddy’s contract, ‘kay? Very legal. Very proper.”

General thuggishness, taciturn unless angered, has a certain sense of self-worth—again, it’s not too hard to guess what Victor looks like, or at least, form an impression of him. Of course, there isn’t much to go on for either character—which is one of the problems of imaginative inference—forming an accurate depiction of a character is going to take a long time, since the character(s) will need to be portrayed in a variety of situations—which can be problematic if you need to establish an important physical trait early on or in a snap. As always with inference, too, there’s the risk of the reader getting the wrong idea and going off on the wrong tangent; one of my beta readers suggested that imaginative inference worked better for parodies because readers are expected to be aware of the tropes and conventions, and react accordingly, and that there’s less chance of misinterpretation.

Furthermore, imaginative inference isn’t very good for details, and should thus be supplemented with breaking up and hiding for best effect, which should also give the more visual readers something on which to anchor their imaginations on (hence dealing with the problem of too little description).

Conclusion

Personally, I prefer having to use mostly imaginative inference coupled with break down and hide for drawing my characters, but that’s just me writing up something I’d read. Again, everything has its time and purpose, and balancing the various methods’ strengths to cover their weaknesses is a skill every writer should have.

Comment [19]

We’ve been presented with Bitterwood, by a certain James Maxey. I’ll confess as to not having read this before, but this is standard operating procedure for most BFT3Ked books anyways—the whole “evaluate as you go along” schtick. Here’s a shot of the cover art, for those of you schmucks who happen to be interested in this sort of stuff.

Hm. Not particularly inspiring, at least from my jaded and cynical point of view, or maybe it’s because of the fact I’m listening to remixed soundtracks from “Zombies ate my neighbours” while typing this out. Anyways, let’s take a look at the blurb:

“It is a time when powerful dragons reign supreme and humans are forced to work as slaves, driven to support the kingdom of the tyrannical ruler King Albekizan.

“However, there is one name whispered amongst the dragon that strikes fear into the very hearts and minds of those who would oppress the human race. Bitterwood. The last dragon hunter, a man who refuses to yield to the will of the dragons. A legend who is about to return, his arrow nocked and ready, his heart full of fiery vengeance…

“Bitterwood plans to bring the dragons to their knees. But will he bring the remnants of the human race down with him?”

This is when I get the popcorn out. Hmm. Evil Dark Lord? Check. Oppressed people? Check. One-man army? Check. Last hope of humanity? Check. Revenge plot? Check. No visible subversion of tired, overused tropes? Check. Of course, book blurbs can be misleading (just look at that of Touched by Venom’s), but more often it goes the other way, and chances really, really aren’t looking good for this one right from the outset. I could have forgiven everything on that list if there’d been just a hint of a subversion, at place, but it seems not. Oh well.

Well. Time for a bit of schadenfreude, then. We’ll see if this is third-grade drivel, or not.

We open in the middle of a peach orchard, in the PoV of a boy named Bant. Heh. Now I’m reminded of DO. Anyways, apparently there’s an ongoing fertility rite to some Goddess Ashera that’s being held in Bant’s Rustic Little Village (you know, the kind which inevitably gets destroyed in order to serve as the Call to Adventure for the hero), and it involves lots of people having sex each other. Seems like this Goddess isn’t all feminist, though:

“In theory, on the Night of Sowing, women were free to choose any partner they wished. In practice, no woman could even refuse any man of the village on this night; to do so would be an insult to the Goddess.” (Pg. 10)

I’m not sure if this portrayal of the Stereotypical Fertility Goddess is intentional, or just a side effect of the whole attempt to inject tension into this “forbidden love” scene, since he’s waiting for his “love” to make it here so he can have her all to himself, and she doesn’t have to be gang-raped by a bunch of men. Mm. So in time, the lucky lady—her name happens to be Recanna—arrives in the orchard, and Bant tries to talk her into going along with the plan:

“What’s wrong?” he whispered, rubbing her back.

“This,” she said, sounding frightened. “Us. Bant, I love you, but…but we shouldn’t be here. I’m afaid.”

“There’s nothing to be afraid of,” Bant said, stroking her hair. “As you say, you love me. I love you. Nothing done in love should cause fear.” (Pg. 11)

Uh-huh. I wonder how many men have said that to women, just before getting her pregnant with an unwanted child. That doesn’t appear to be an issue here, though; Recanna is more afraid of going against the rites of the Goddess and calling down punishment for their sins. anyways, they’re about to do the deed when they spot a light on the road leading into the village. Apparently this isn’t a good thing, because lights aren’t supposed to be lit this night, and the two of them are wondering on whether this spells doom for the village when Jomath, Ban’t‘s Evil Elder Bullying Brother, turns up.

Whee. Naked Good Woman. Evil Bullying Man. One doesn’t need to be a rocket scientist to figure out what happens next. Invoking the name of the Goddess (of course, not because he really believes in her, but just as a justification), Jomath proceeds to beat the shit out of Bant, taunting him all the while, and then there’s a whole half-page of DARK RAGE on Bant’s part, after which Jomath proceeds to almost-rape Recanna. Because y’know, it’d be too horrible if she actually got raped, since she’s the Designated Love Interest and everyone knows that the Designated Love Interest must have his/her (but more often her) first time with the protagonist, and it’ll be the Best Sex Ever.

But more importantly, here’s a small question: why does the OMGDARKRAGE work in DO, but not in here? What’s the difference between RuGaard’s OMGDARKRAGE and Bant’s OMGDARKRAGE that the former inspires actual anger on the part of the reader directed at the character/s the author means it to (in the former case, the rest of RuGaard’s family, in this case, Jomath)? The answer is simple: in DO, we’re allowed to sym- and empathise with RuGaard first before he goes and has his fits of OMGDARKRAGE. We’re allowed to make up our minds, get enough information as to whether the OMGDARKRAGE is justified, and most importantly, I didn’t get the vibe that the author was trying to arm-twist me into feeling one way or the other.

Compare it to here—three pages into the narrative proper, and we’re already getting our arms twisted by Mr. Maxey. I don’t know why I should be caring about Bant or Recanna; Mr. Maxey’s just banking on the automatic rape of a woman = bad reflex in an attempt to produce sympathy in readers. It’s not stupid, because it does work on an undiscerning audience, but it damn well is lazy. I have zero emotional connection with any of the characters; they could die this very moment and I couldn’t care one whit less. It’s only made worse by the fact that Mr. Maxey has to resort to the stupidest of stock tropes for a minor character and make him a one-dimensional satellite character grates on the ol’ sensibilities, not to mention I’m getting the impression here Recanna is being fought over like a trophy to be had.

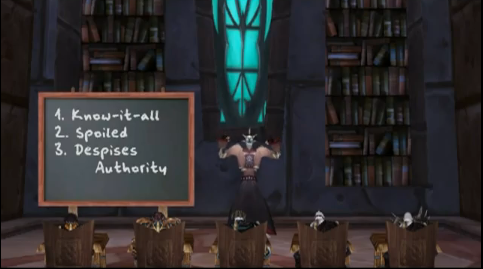

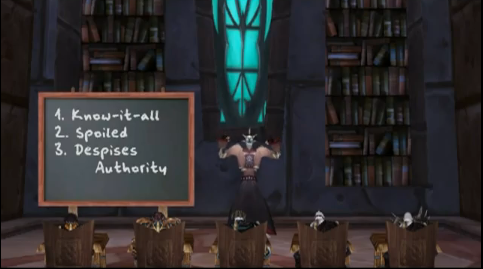

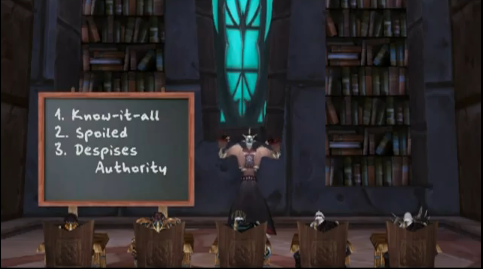

Maybe I’m reading too much into this, but the end result is the same: instead of being afraid of and for Bant, he’s now just a stupid emo, and if you’ve read my drabbles on first impressions, this is going to have lasting damage on any future analysis. Yes, there’s a fine line between working and not working, between cheesiness and and being truly intimidating, but there’s no reason why it can’t be walked, considering that good authors can do it consistently and without requiring the so-called “standard” tools, which more often than not are counterproductive (not a book example, but see Seymour Guado from FFX, which after a bit of toning down to make believable, could have worked very well. Too bad SE just HAD to make him over-the-top).

Anyways, there’s a scream from the direction of the village and from the orchard they can see a huge bonfire burning in the middle of the village. Ayup. You know what’s going to happen here. Conveniently for Recanna’s virginity, Jomath drops the matter, and they race back to the village, but not before more Informed Attribut-ing:

“Alone, Bant could have outpaced Jomath, even with his head start. Jomath had gotten all the brute strength in the family, but Bant’s slight, wiry build made him the fastest runner in the village.” (Pg. 16)

Because, as we all know from RPGs, big people can’t move quickly. Yes, you will tend towards a lean frame if you run a lot, but lean does not mean you can’t be big, and it damn well doesn’t mean you can’t move fast, or else no one would watch heavyweight boxing. End of story. What I’m bitching about here is a) the mindless adherence to stereotypes and b) the telling style of the narrative used here. The three of them get closer to the village, and on their way back, just outside the village is a big black dog tethered to a cart.

That’s right, a big black dog. As big as an ox. Which smells like rotting meat. And belongs to the Evangalist Strawman.

…Facepalm I know Christianity’s an Acceptable Target right now, but why don’t authors go and kick another Acceptable Target for a change? Like hetrosexual white men, for example? Or people of oriential descent? Or megacorporations? When I read this for the first time, I was already thinking “all right, I know how this is going to go.” And true enough, I was disappointed in everything but my expectations.

But that’ll be covered when we go across it later. For now, what we get is a two-thirds page description of the Generic Fertility Goddess’ temple, which we will never see or interact with again after it gets burnt down, which it it doing right now. Anyways, our dear Evangalist Strawman comes out of the burning temple with the statue of the Goddess, plonks it right in front of the villagers, and recites the First Commandment in “a thunderous voice”, before taking out an axe and cutting off its head:

“It may be,” the stranger growled, “that you dwell in ignorance, and are unaware of your sin.” He lifted the heavy tool with a single hand high over his head. “I have been sent by the Lord to show you the way.” The axe flashed down like lightning, splitting the Goddess in twain. (Pg. 18)

Clap clap clap clap Of course the people of the village don’t like that, and they all bugger off to swarm him. All their blows come to naught, and the EVIL BIG BLACK DOG happily slaughters them down to the last man, all while Bant and Recanna watch on. We’re supposed to get the idea that Bant is an antihero, because he supposedly feels nothing for the people being slaughtered, even those of his own family, but it isn’t working. Some of this can be explained by the sheer amount of telling that’s going on and the idea that the author expects me to take everything he says about his characters as gospel, part of it can be explained that I STILL don’t have any sympathy or even empathy for Bant, and another part can be explained by the plain fact that I’m already hating this story and am disinclined to like it any further, which only goes to show the importance of getting off on the right foot.

Anyways, when the carnage is done, our Evangalist Strawman dismisses the dog and walks up to Bant and Recanna, asking their names. After that little formality, Mr. Strawman forcibly marries the two of them, telling them “do not question the commandments of the Lord”. We learn that Mr. Strawman’s name is Hezekiah, Bant gets a copy of the Bible, and he’s to be taught how to read. Of course, him actually learning to do so is skipped over. More blah as Bant and Recanna kiss, and we end the prologue with this head-banger:

“This is how Bant Bitterwood learned that hate could change the world.

This is how Bant Bitterwood found God.” (Pg. 24)

Twitch Thanks for insinuating that God = hate.

Where should I start? I’m not even a Christian, I’m an agnostic, and this pisses me off so much. Christianity-bashing in the genre is so stupid, unimaginative and overused that the moment a single Christian Strawman appears on-scene, that’s it; we’re going to get treated to a whole sideshow of wonky antics that’d put real-life Islamic Radicals to shame for not trying hard enough. Hezekiah turning out to be a Really Advanced Robot later on doesn’t mitigate it any. It’s just like the Red Queen in Dragon Strike. You can put the shit in a different bucket, you can make your stupid villain a squid from the butter jelly dimension of Atlantis, and in the end, it’s still a stupid villain, it’s still the same stupid shit.

Hell, it makes it even WORSE, since all the “thunderous voices” and “protection of faith and god” turns out to be really because he’s a Really Advanced Robot. Which falls neatly in line with the “religious people don’t really believe in their religion, but merely use it as an avenue to power” paradigm. Hezekiah later reveals that a) he knows he’s a robot, since he needs to make repairs to himself and b) he has a maker that isn’t God. It’s insinutated there that whatever small measure of belief he has, it’s just there because he’s been programmed to do so, and he doesn’t have much at that.

Great job being prophet of God if ten centuries of being a prophet still ends up with Christianity being a no-name religion in this conworld; Christianity only took a few hundred years to become the official religion of the Roman Empire. Oh wait, he destroys anything he touches.

All of the above could be true and a reflection of our world. All real-life evangalists could be evil robots working out to destroy all we hold dear in the name of some religion. And it’d still be unimaginative and stupid to follow the conga line of Christianity-bashing in the genre.

And DO authors even THINK of the implications of what this means for the conworld? The existence of Christianity and the Bible mean that this has to be some post apocalyptic-version of Earth, since I don’t remember Hezekiah crashing in a space pod onto the planet’s surface. First off, that means magic as it’s commonly understood, and not “television shown to cavemen” is flat right out of the equation. Then, you’ve got basic physics of Earth, which dictate that there’s a limit to the weight versus muscle cross-sectional area ratio (which determines strength), and the heaviest flying bird on Earth is ten kilogrammes. That means the dragons, flying as they are (not gliding), are RIGHT OUT.

Then we have all the stupidity, like the English language being used exactly as we know it today after a thousand years at least, which is incredibly stupid given linguistic evolution, and the question of why the paper-and-ink bibles haven’t fallen apart, and—

—You know, at least most post-apocalyptic settings spend a lot of time addressing these questions.

——

And here’s the minor rant:

You know, I really, really am wondering about the diametrically opposing suggestions in having a borderline Sue, who happens to be not just a Paramortal psychologist dealing with the mental problems of all sorts of supernatural creatures (from vampires. And werewolves. And ye typical Fae. Maybe if we got a Jiangshi or Potianak my eyes wouldn’t glaze over so badly, but I understand the book’s written for a western audience), when dealing with the psychological problems of humans is already tricky enough ground. Oh, then there’s the fact that said Sue is a Marine Special Forces Operative who “can get physical with them when the situation calls for it”.

Fine, whatever. I won’t go into that now.

Alas, the cover art appears to be dedicated to a blond bombshell in a tight-fitting singlet and jeans. Said blond bombshell is of course, physically perfect without the excess musculature you’d expect of someone in excellent physical condition, either bulky or wiry, a nice hourglass figure, and the pose said character is in is perfectly positioned to let anyone looking at the cover art get a nice view of her approximately 42DD-E sized mammaries, complete with gratituous amounts of cleavage almost right up to the nipples. Which doesn’t make sense, since most women who work off all that fat don’t usually have enough left over to get very big mammaries, especially if they do a lot of running. When was the last time you saw a female athlete with anything over a B?

…Yeah.

Oh, and did I forget to mention the very manly-man vampire brothers she has a love triangle with? Very manly-man indeed. Oh, and she gets captured and needs the manly-man vampire brothers to save her, whereupon they fight over her. Actually, they fight over her for pretty much the whole of the story.

…Really, every single UF story is starting to look the same. The ones with female protagonists always involve kick-ass girls who happen to come into contact with very manly-man male-types and get into psuedoromantic relationships, while the ones with male protagonists seem to always involve poverty-stricken private detectives who live at the edges of society, both mundane and supernatural, and who all have tortured secret pasts.

Gets out sandvich Nom nom nom, om nom.

Comment [15]

Note that this chapter was originally done in two separate bits, but I mushed it together for your reading convenience. That’s why the Failcount resets after Bant’s scene.

Chapter 1:

We open with Bant, in the middle of a wood. Of course, I know it’s Bant, but for some reason, the prose insists on referring to him as “the hunter”. This worked in DO, because at that moment RuGaard didn’t have a name and it was specifically meant to point out the fact that said not having a name would scar him for life (or at least, according to Mr. Knight), but here, I don’t see any reason for witholding Bant’s name, except perhaps in an attempt to be mysterious. I mean, come on, don’t you think “hunter” is deep and mysterious? Like “raven” or “wolf”?

Ahahaha. In any case, it’s merely causing confusion and making Bant less of a character that the reader can immediately identify as the PoV character. Congratulations. Anyways, Bant’s all pleased with himself over having brought down a sky-dragon, and we get a whole page of unbroken description right three pages into the introductory chapter. Holy shit, Batman! Before I have any reason whatsoever to care about how these dragons look like!

I’m being serious here. Eyes glazing over serious. Pointless infodumping is one of the cardinial sins of contemporary fantasy fiction, and while it might be information you need to get across, one unbroken page of solid description is not the way to do it. Because, y’know, INCLUING is impossible, or even giving the information in broken dribs and drabs. As much as Mr. Maxey is desperate to get the message across, we don’t need to know everything about sky dragons right now, thank you very much. How about introducing it naturally a little while before it’s actually needed, so while it doesn’t seem like a pointless throwaway reference, it doesn’t seem like something made up on the spot to justify something, either?

Blah blah, more exposition on how the sky dragons consider themselves artists, blah blah, feathered scales, blah blah, how they think it’s beneath them to hunt, blah blah. In any case, Bant picks off the dragon’s backpack (yes, it is a “leather satchel”) and rifles through its contents:

Bant receives items:

-Bottle of wine x 1

-Peasant loaf x1

-Eel jerky x1

-Horch, which is a paste made from sardines, olives and chillies, all fermented. x1

-Book of nature studies, beautifully illustrated x1

-Writing materials x1

…Where’s the Captain Picard facepalm when you need it? Given the way the sky dragon was described, half the shit in its backpack would be wildly inappropriate. First up: bottle of wine. By all means, this bottle is what we humans on Earth would recognise as a bottle, since there is no information to the contrary. Now, bottle. “Crocodilian jaws”. Bottle. “Crocodilian jaws”. Do they fit? Of course not. Unless they were dumping it in their mouths, and then there’d be no way to control the flow (which these oh-so-civilised and refined sky dragons wouldn’t like), there is no way one is getting wine from bottle into “crocodilian jaws” without a LOT of spilling. Necks of bottles were designed for people with LIPS. Fail x1.

Next up, hard peasant loaf. Requires sopping and chewing. A LOT of both sopping and chewing. “Crocodilian jaws” are NOT made for chewing, which is why they can regrow the odd tooth when one gets knocked out—biting precision isn’t important for such a jaw model, which also explains why we humans and plenty of other mammals only grow limited sets of teeth. Crocs use their teeth for grabbing prey, killing them and biting chunks off whole. Fail x2.

Eel jerky. Fine. No problems. Ditto horch. Now it’s time for book of nature studies. In linen paper. By people with sharp, two-inch claws.

Can you see the problem here? Fact of life: people handle objects roughly. Maybe they’re tired, or they slipped, or an accident happened. Whatever the case, even amongst us humans who keep our nails fairly neat and trimmed, books get damaged, books get torn. Now imagine people with two-inch-long sharp claws. Parchment and paper ain’t going to last long. Fail x3.

Writing materials. I’m having trouble figuring out how people with two-inch claws on each digit would conventionally hold a pen in a fashion that approximates us humans, since the pen is described as a quill pen, but I’m willing to give this a pass. For now.

Already, I can tell from this the amount of care and thought which Mr. Maxey put into his worldbuilding, which is absolutely none at all. He just took humans, stuck on wings and all the other bits, and declared them done when as I’ve mentioned before, merely changing the physical alone has a massive ripple effect into the social, mental, spiritual and other worlds. Mr. Maxey didn’t stop to consider how the differences in physical attributes would affect his dragons, even if they’re more on the lines of humanoid furries rather than the traditional hexapod quadrupeds. Even Limyaael points out clearly in this rant that the simple addition of wings to humans will require plenty of thought and change from what we know and think of as “human”.

But evidently, someone didn’t care. Fail x4.

Anyways, Bant is all cold and dark and gloomy, and he slices out the sky dragon’s tongue and goes om nom nom on it after having built up a fire, then he goes and burns the nature studies book, but not before contemplating writing a letter home:

Opening the bottle of ink, he dipped the quill and drew a jagged, uneven line upon the page. He tried again, drawing a circle, the line flowing more evenly this time. Across the top of the page he began to write “A B C D E…” and it all came back to him. (Pg. 28)

Congratulations. Thank you for ruining what pathetically little immersion I had, if I had any remaining. Thank you for dragging me out of your conworld and plonking me right down into the real one. Thank you, Mr. Maxey, for completely neglecting and ruining any sort of linguistic evolution, if you’re going to go the route of “this is really post-apocalyptic earth!” People in the early 1900s spoke very much differently from how we do today, and that’s within the same language. Just imagine…ugh. I don’t even care. You hear me? I don’t care anymore. LALALALALALALA.

Fail x5.

We get more glimpses of Mr. Maxey’s wonderful methods of characterising his anti-hero protagonist:

Here the hunter stopped. If only. These were weak words, regretful. They had no room in his heart. This was not a night to lose himself in memory and melancholy. Tomorrow was an important day.(Pg. 28)

Thank you for telling me all that, instead of showing it. Would it have been too much to ask to let me interpret his emotions for myself? And really, there’s wanting your protagonist to be a cool antihero, and there’s trying too hard. Mr. Maxey is definitely trying too hard. You see, no matter how un-heroic your character is, you still have to have some measure of em-and sympathy for your character. You can’t make your character completely unlikable—I’m very sorry, but trying to get the readers to read on by making them hope something terrible will happen to your protagonist generally isn’t a good idea, and that’s what seems to be happening here.

Coming back to the point of DO, RuGaard is very definitely an anti-hero, given his whole life is built on lies, his complete misanthropy and bouts of pure, unadulterated hate and in the end, deep suspicion of even his own wife. Yet he’s likable. There are good traits that are played up, not-so-good-but-not-bad traits that form the crux, and most importantly, we’re given to understand why he does what he does.

Second example: Rocky and Freckle from Lackadaisy Cats. Rocky is clearly crazy and has dome some not-very-nice things in his time, while Freckle is a cute little mild-mannered kitten-face who happens to go batshit insane in the presence of firearms. Both of them happen to be morally dysfunctional at least part of the time and certainly qualify as being anti-heroes (being rumrunners would probably have done the trick alone), but they’re likable to some degree.

Let’s say I’m a reader who hasn’t read the book blurb; right up to page 29, I have not seen a single redeeming quality about Bant. Oh, Mr. Maxey tried to arm-twist me with Jomath all right, but that does NOT work on me, and this impression of Bant is not going to go away quickly. Fail at properly introducing anti-hero. Fail x6.

Anyways, Bant watches the rest of the book burn.

In any case, we leave Bant behind and get a scene change to the great hall of King Albekizan. However, from now on I shall refer to him as Evil King, since that’s as far as his characterisation goes. Of course, the PoV character happens to be a human woman by the name of Jandra, who happens to be the apprentice of Evil King’s court magician, Vendevorex. Apparently, this is allowed because Vendevorex is SMRT, but of course, up to this point I have nothing to base this on except for Mr. Maxey’s word for it, and you think I’m going to believe that something in a story is so just because the author says it is, rather than on how the character actually behaves? Minor fail x1.

Fat chance.

Besides, historically, one class that relies on the subjugation of another was nautrally very jittery about the subjugated class getting their hands on education and positions of power, for obvious reasons. And given the way the Evil King is characterised as we’ll see shortly, I doubt Jandra would be given the chance to even survive, let alone appear at his court, even as someone’s pet. But what do I know? I’m just a guy who cares about logic. At least the courtiers have the sense to disdain her.

In any case, there’s some description of the great hall. Jandra’s wearing a satin gown with an elaborate peacock headdress…yadda yadda…dragons lounging around on silk mats…yadda yadda…description of sun-dragons…yadda yadda…drummers, choir…golden cushions for Evil King and pillows for the Queen…

Wait, what?

I’m not even sure what fabrics are doing in the same place as a room full of people with rough scales, sharp feathers and talons. You asking me why the fabrics aren’t already ripped and torn all over? You really asking me? Well, my theory is that there was a mass happenstance of Solids Toughening Under Pre-Induced Duress, or STUPID for short, which allowed the fabrics to escape unharmed. Of course, it’s just a theory, although there’s already been substential evidence to back it up. Fail x1.

More pointless description (hey, you get the idea) flows by, and then the Evil King’s High Biologian (no! The correct term is “biologist”! “Biologian” isn’t even a word! Minor fail x2!) comes out, and we get the following snippet, which sadly, is rather characteristic of how Mr. Maxey likes to write his prose regarding his characters:

He hobbled forward, supporting himself with a gnarled staff. Despite his stooped, crooked body, Metron commanded respect. Everyone present lowered their eyes in reverence. (Pg. 31)

Holy redundancy, Batman! Not only does Mr. Maxey tell, he shows AND tells, therefore making one of them redundant! You see, if everyone lowers their eyes, especially in reverence, I can INFER that they respect him and so don’t need to be TOLD as well that they do so! If I’m TOLD that they respect him, under the right circumstances I would accept it, but you don’t need to SHOW at the same time! It’s almost as if Mr. Maxey thinks readers are retards and can’t figure the simplest of things for themselves. Minor fail x3.

And a cane? A CANE? This is quite possibly our first suggestion that we’re dealing with more “anthro-furry” dragons, rather than your conventional quadruped hexapods. Upon reading this for the first time, I had to stop and think about why the hell a quadruped creature would fucking need a cane for, and that dragged me once again from my pathetic attempts to immerse myself in the—oh, who am I kidding. The thing is, if Mr. Maxey had bothered to make it clearer in his lavish descriptions of sky and sun-dragons that they differed from the typical portrayals, there wouldn’t have been this problem.

And don’t give me that shit of “aren’t you the one who complains about cliches?” Because I’m not arguing against the subversion, but rather, on how Mr. Maxey handled it—by saying “elf”, “dwarf”, “goblin”, or anything else, you ARE going to evoke pre-conceived notions and templates about said species in the minds of your readers, and it is vital to establish how YOUR interpretation of these so-called stock fantasy races differs from the templates before you actually put them in action. Fail x2.

More description of Metron being presented before Evil King. Particularly egregious excerpt:

The strength in Metron’s eyes allayed her fears. (Pg. 31)

Telling and a pathetic attempt to use physical description in lieu of actual characterisation, but I already covered that. THE EYES DO NOT HAVE IT. By now, it’s best to completely avoid using eyes to make any sort of “deep” statement about a character. Minor fail x4.

Anyways, directly after that, we get a full-half page of description regarding Bodiel, Evil King’s younger son. Blah blah, arrival, flowery prose, blah blah, I don’t care any more. Note that after three pages of this scene, we still have no idea what this ceremony is supposed to be about, nor has anything happened, considering all three pages were almost chock-full of description of the scene in Evil King’s great hall. Great pacing. I feel no connection for Jandra or any of the characters introduced here; it seems as if Jandra’s only here to provide a pair of eyes for the—oh, wait, that’s probably the ONLY reason she’s here. But that’s not the worst thing. After the Obnoxiously long and pointless description of Bodiel, we get this kicker:

Jandra’s heart fluttered at Bodiel’s beauty. (Pg. 31)

…Getting back memories of Touched By Venom.

…Oh god.

DO NOT WANT. Fail x3.

Anyways, Metron begins the ceremony proper with the ritual greeting, which seems like a whole lot of sycophantry, but hey, I guess he’s not to blame for the way it’s worded. At last, we manage to learn what all this hoo-hah is about, even if it takes us a bit of head-hopping. Ready for the great reveal? Apparently there’s a ritual in which the sons of the Evil King compete to see which has the honour of being banished from the kingdom. Yes, really. Supposedly, the hope of this is that the banished sons will return to overthrow their fathers, and hence rule with even greater strength, and supposedly this practice has kept the Evil King’s line in power since time immemorial.

Facepalm Let’s pick this apart one problem at a time, shall we? 1. Learning proper statesmanship and the ins and outs of running a country isn’t very well done when you’ve BEEN BANISHED. (Where to, though? The way things are set up, it seems as if the whole world is this kingdom, anyway) 2. It never states how the son is supposed to do the overthrowing against a whole kingdom, which them would be a pointless quest if he had to go solo. 3. Having no clear line of succession is obviously not good for the stability of any country, and 4. What if a king fails to produce male, or indeed, any issue at all?

This is one of the things which sounds like a great idea, until you dig a little deeper and realise the only place where it could be taken seriously would be in a parody. Fail x4.

More wonderful characterisation by Mr. Maxey:

The king’s youngest son, Bodiel was universally recognised as the dragon most likely to best his father. He was strong, fast and charming, a master of politics as well as combat. Shandrazel was larger and, most agreed, smarted, but few believed he could previal. bodies possessed the will the win at all costs. The lust for victory boiling in his blood rivaled Albekizan’s and perhaps even surpassed it. (Pg. 33)

(Gets out sandvich) Nom nom nom, om nom. I don’t think I have to repeat myself as to why this is bad. Fail x5. Finally, we learn what the competition consists of; two slaves are going to be released into the woods, and the kiddies have to hunt them down and presumably kill them. Hurrah hurrah. So the cages are opened, and the slaves run into a tunnel which leads into the forest, but not before Mr. Maxey shows off his excellent ability to convey characters’ emotions:

Jandra again felt a stirring of guilt. She was in awe of the ritual she was witnessing, swept up in the grandeur. Shouldn’t she feel some remorse over the fates of the slaves? (Pg. 34)

I rest my case, and will only point out the worst violations of this bit of general writing knowledge. Or perhaps not. Heh. Minor fail x5. At least what we’ve had so far hasn’t been TOO bad, but Evil King opens his bloody mouth for the first time and perfectly justifies why I’m calling him little more than Evil King:

“Humans these days are worthless,” Albekizan said, addressing the High Biologian. “In my youth the humans had more spirit. They were alwyas finding sharp rocks to wield as weapons, or hiding in tiny caves. I remember how one doubled back and hid within the palace for two days before being captured. Now, the slaves run blindly, leaving a trail of excretement any fool could follow. Why can’t we find good prey anymore, Metron?” (Pg. 34)

…

(Takes another bite of sandvich) Nom nom nom, om nom. I don’t know about you, but after reading this paragraph, I can’t help but be reminded of the worst of caricatures. Is it too much to ask for an antagonist who isn’t a gloating idiot? Again, Mr. Maxey’s determined to arm-twist me into hating Evil King by placing him so far on the scale of conventional western morality that I have no choice but to dislike him, because god forbid someone be affably evil, if they have to be evil in the first place. Well, guess what? I’m equally determined to say “fuck you” to such cheap tactics. Fail x6.

Of course, the High Biologian points out that humans have been systematically culled for a long time, and that “the breed must inevitably decline”. Vendexorex, of course, putters along and suggest the hunting of humans be temporarily stopped to “let the stock recover”. Uh. Whatever. Of course, this provokes another over-the-top response from Evil King:

“Bah!” Albekizan snorted, raising his bejeweled right talon dismissively. “You and your softness for humans. They make fine pets and adequate game, but you would let them breed like rabbits. The stench of their villages already sullies my kingdom.”

“Their villages fill your larders with food and your coffer with gold,” Vendevorex said. “Allow the humans to keep more of the fruits of their labours, and they will improve the conditions in which they live. They dwell in squalor only because of your policies.” (Pg. 35)

Ah, yes. Whoever could forget the number one evil tool of any evil regent: taxes, taxes, taxes. Perhaps I could be persuaded to care more if I actually knew what evil policies were in place beyond the absolutely generic ones and saw them in action; at least the Generic Little Village which gets destroyed by the Dark Lord’s legions of terror happens to show them in action. If this turns out to be another Inheritance with everyone (everyone who is good, anyway) talking about how evil the Evil King is without actually seeing some of the bloody repression of the common man in action, I have nothing to say.

Of course, in a typical Evil King fashion, Evil King gets pissed at advice of advisor that doesn’t match his preconceived notions. How exactly someone who happens to be so much of a bloody idiot happens to have held power centuries is beyond me; authorial intervention, probably. I’ll just quote Limyaael on this:

“It doesn’t make much sense to have stupid people conquering the world. Either villains are really secretly intelligent until the hero comes along, at which point their wits drain away, or everyone else who tried to resist evil in the past was monumentally idiotic. The hero always seems to be not only more intelligent than his nemesis, but supremely more intelligent than his nemesis.

How did the nemesis become a nemesis, then?

Think about it. If the dark lords in fantasy really failed as badly most of the time as they do when confronting the heroes, their reigns should have ended centuries ago when they did something like leave a large and obvious loophole in their plans that their enemies could slip through. Lack of intelligence turns them cartoonish.”

Fail x7.

In response to that, Vendevorex pulls the “you commanded me to speak freely in the past and haven’t rescinded that order” stunt. In any case, Evil King swallows what he was about to say and orders the hunt to begin. Bodiel’s off in a flash, but the other son, Shandrazel, refuses to take part:

“You know my feelings. I do not desire your throne. I will not hunt Tulk. This ceremony is archaic and cruel. There is no need for blood to be shed. Simply appoint Bodiel as your successor. Your word is law.” (Pg. 36)

Stilted language aside (I mean it. Try saying this out loud. Do you think it feels natural at all?), it’s interesting to note that in a supposedly non-anthrocentric world, morality is still defined by who likes humans and who doesn’t. Wonderful, isn’t it? Vendevorex and Shandrazel are Good because they like humans, and reversely, anyone who doesn’t like and looks down on humans are portrayed as utterly horrible and evil.

It’s also interesting to note that Shandrazel also shrugs—which even if it’s technically possible due to a bipedal humanoid body structure (which I still have problems accepting, considering that body structure can only support so much size and weight before the leg bones, no matter how dense and strong they are, and note that most flying creatures often have hollow bones to reduce weight—oh, why am I even bothering? Remember that the heaviest flying bird on Earth is 10 kilograms? But—but this isn’t Earth, and physics doesn’t apply here—but they’re using English, and Christianity’s around, even if it’s only an Evil Robot, and…and…does not compute. Does not compute!), the shrug is very particular to modern western symbolism. Why non-humans should blindly adopt it—oh wait, these dragons are really people with parts glued on. Silly me. Fail x8.

So Evil King and his elder son have a staring-down contest, but not before this particularly horrible outburst:

“And you are breaking that law!” Albekizan shouted, spittle spraying the floor before him. “I command you to hunt!” (Pg. 36)

Oh noes, oh noes. Spluttering villain, which brings in a whole bunch of ugly connotations. Fail x9. Anyways, the staring match goes on for a while, which doesn’t really make sense if Evil King was willing to kill off the previous two sons who got banished. Why spare this one and go against what little characterisation Evil King has been given? It doesn’t make sense, really—oh wait, if Shandrazel died, the resolution at the end would be impossible, so Evil King must be an idiot and let him off.

This, my friends, is what we call an idiot plot—where the characters must act like idiots to keep it on the rails. Fail x10. So the staring match continues, when the Queen suddenly leaps up and shrieks that her son’s dead.

(Yet another bite from sandvich) Nom nom nom, om nom. Evil King breaks the staring contest to comfort her, and we get a prime, overmelodramatic example of what I personally call “the pathetic fallacy” and some others call “sadrain”. In short, it’s the manipulation of the weather to heavy-handedly set the mood:

Almost as if his saying had made it so, the night fell quiet. The thunder faded and the wind shifted, silencing the rain for an instant. At this moment, a mournful, anguished howl rose from the distant forest. Lightning flashed and thunder washed away the voice. The wind twisted, whipping back into the hall with a harsh blast of cold rain, sending the torch flames dancing wildly. Tanthia gasped as one of the torches extinguished, a soul forever lost.

“He’s dead!” Tanthia cried. “My son is dead!” (Pg. 37-38)

(Finishes the sandvich) Nom nom nom, om nom. Well, that certainly was melodramatic. Since I mostly share Limyaael’s thoughts on this, I’ll just quote her:

_“I tend to distrust this technique. As you said, it can be done well, but it’s very hard. It’s even worse when the author takes note of it (as in one of the DragonLance Chronicles, where Weis and Hickman actually note the rain is like weeping). When it doesn’t work, it’s another heavy-handed way of the author telling you how to feel about her characters.

I think it can work when the author’s already established that a particular weather pattern is normal- someone weeping in what you’ve already been told is a monsoon season, for example- or when it’s used as irony, such as a bright and cheerful day on which a battle happens.”_

Well, I can safely say that in my opinion, it damn well didn’t work. Minor fail x6. Noting that things are going pear-shaped all of a sudden, Vendevorex and Jandra make a hasty retreat, the former sprinking magic powder over them both to make them INVISIBIBLE. I know that Mr. Maxey really wants to show off his character’s skills, but this seems hardly an appropriate time for such a trick, and the courtiers seem to have the attention span of a gnat, since they’re all immediately in awe of said trick instead of, y’know, being concerned about the drama, especially in the presence of an plot-convenience horribly contrived insane king.

So they’re gone, and Shandrazel flaps off in search of his brother. We get a whole page’s worth of Mr. Maxey’s Wonderful Characterisation Format, by now which I’m sure you’re familiar with, so I won’t elaborate. The only bit I want to point out is that his mother eats baskets of white kittens by the truckload. Yes, really.

Despite his father’s keenness for the sport of hunting humans, Shandrazel saw no more challenge in it that he did in his mother’s appetite for devouring baskets of white kittens. (Pg. 39)

All fucking right, they’re fucking evil, fuck it. You don’t have to fucking make them EAT FUCKING KITTENS to TELL ME HOW FUCKING EVIL THEY ARE. Stop it, stop it, STOP IT. Fail x11. Anyways, he putters around to come across the sky-dragon’s body we saw just now. Some pointless blahs about how this guy used to be his old teacher, blah blah, more pointless blahs, and then he and Evil King do some more searching until the come across Bodiel’s body. Let’s take a look at his reactions:

Albekizan’s eyes burned with fury, fury and something more, an emotion he’d not seen in his father’s eyes for many years: passion. Albekizan, cradling Bodiel’s dead body, was filled with frightening, fiery life. (Pg. 40)

Lightning struck nearby, again and again, shaking the ground. Fire spouted from the tops of the tallest, most ancient trees. Albekizan didn’t flinch. Shandrazel couldn’t move. As the thunder faded from their ringing ears, Albekizan held the arrow to the sky and shouted a single, bone-chilling word.

“Bitterwood!” (Pg. 41)

There are so many problems with this that I don’t know where to start. Again, overly melodramatic, making it completely cheesy, and the pathetic fallacy only makes it worse. Minor fail x7. Now for the important part. Evil King has been characterised as evil. Doesn’t care about subjects, both draconic and human. Kills own sons. Does lots of evil and bad things which we haven’t seen yet. And we’re supposed to believe that he’s the type to love this particular son all of a sudden? Are you kidding me? You don’t just mangle your characters’ characterisation like that just to further the…oh, wait, this is an IDIOT PLOT. What was I expecting? I could have seen Evil King taking this as an insult to him, but his actions suggest otherwise, and it’s explicitly stated in the book blurb that he’s supposedly avenging Bodiel. So, no. Mangled characterisation. Fail x12.

Then we get on to the bigger problem: WHY WERE THERE NO GUARDS AROUND THE PALACE? You know, traditionally, most palaces, even summer/winter ones, were very well-guarded—heck, it’s where the bloody head of state lives. You’d expect there to be a patrol at all times. Forest? Most royal forests, or the equivalent thereof, had a forester or two—people whose job was to live in the forest, know its ins and outs, keep out trespassers and poachers, and make sure it was fit for use whenever the nobility fancied a bit of sport. Oh, there’s one we’ll see in the next chapter—a buger by the name of Zanzeroth. WHAT THE FUCK WAS HE DOING? HOW WAS BITTERWOOD ALLOWED TO GET SO CLOSE—oh, wait, SHEER INCOMPETENCE ON THE PART OF THE ANTAGONISTS TO ADVANCE PLOT. You know, I wonder why he didn’t just lie in wait and smack Evil King with an arrow as they searched for Bodiel. Oh, wait. If he did that, there’d be no story. Stupid me. Fail x13.

One more point: How did Evil King know conclusively it was Bitterwood? It could have been the fletching on the arrow perhaps, since it was studied for a bit, but it’s never conclusively explained. Besides, it could dang well have been someone else impersonating him. There’s some ambiguity here, so I’ll give our dear friend the benefit of the doubt here, but a few WORDS to make it clearer wouldn’t have hurt.

And so we end this disgusting tripe which is an excuse for a chapter. End of round: minor fail x7, fail x13, epic fail x0. Total fail score: 7 + 13*3 + 0 = 46.

Comment [21]

Chapter 2:

To be honest, I’m now very tempted to give a cameo in MA to a minor hero named Batterwoad. He will try too hard to be evil and anti-heroish, utterly fail at it, as well as utterly fail at killing Victor, who has something of a brain.

Well, it’s the same night, and we find ourselves in the woods in the PoV of dragon slave by the name of Gadreel. Apparently, his master, Zanzeroth—who appears to be forester, hunter and tracker rolled into one, you know, the common “woodsman” template—and Evil King are scouring the forest for signs of Bitterwood. As I’m reading the prose of their search, I can’t help but get the feeling that it just doesn’t flow, that the prose itself, like the characters’ dialogue, is bloody stilted, but since this is admittedly rather subjective, I’m not going to be assigning any sort of fail to it. A small sample to prove my point:

Albekizan stood nearby, watching the aged hunter step gingerly over the muddy ground. Albekizan ignored Gadreel. Gadreel hoped the king’s snub was due to his fascination with Zanzeroth’s methods. (Pg. 42)

Well riddle-dee-dee. You expect me to believe Gadreel’s been a slave for the past three years when he’s not used to the high and mighty ignoring him, least of all the bloody Evil King who’s supposed to be horribly cruel to everyone? Again, it’s not showing thought or any research into the mindsets of most slaves which unfortunately, tend to go against uprisings and the like. Minor fail x1.

Anyways, we never see Zanzeroth’s mad tracking SKILLZ in action (besides him making proclaimations about how events turned out, with the occasional footprint), and this is supposedly because Gadreel knows jack shit about his master’s work, but I suppose that after three years in his master’s service, it would be impossible for even a slave to pick up on bits here and there, would it? But fine, I’m willing to give this a pass. We get a half-page dump of description about Zanzeroth (who, of course, is rugged. Because all woodsmen, with the exception of elf woodsmen, are rugged.) Zanzeroth asks about Shandrazel, and this is what Evil King has to say:

“Do not speak that shameful name,” Albekizan said, his eyes narrow. “I’ve placed that traitor underguard for now. His final fate will be left for the morning. We will not discuss this further. For now, Bitterwood is our only goal.” (Pg. 43)

Again, the eyes do NOT have it. I could excuse narrowed eyes, as they’re very common and a bit hard to find a substitute for, but it’s still an itch I can’t scratch. That’s not the main problem, though; the main problem is that Evil King’s concern for Bodiel is seeming more and more contrived by the moment. We’ve never been given any reason why someone known for killing off his own sons should favour the one most dangerous to his continued regime, and Shandrazel doesn’t seem to be any better off. Maybe Mr. Maxey is trying to “humanise” Evil King by making him love his son, but it doesn’t work because 1) even if it did, one white spot in a sea of black isn’t going to do jack shit, and 2) it crushes any consistency in the characterisation to hell, making it seem as if Evil King does what the plot needs him to. Fail x1.

And I’m just wondering, just under what reasons Shandrazel is being charged with treason for. But that’s just me, wondering too much about stuff again.

Another problem here is the CSI-style reporting of Zanzeroth. Supposedly, this scene is intended to be tense, with them pursuing Bitterwood as he flees the scene, trying to catch him before he makes it to safety. The fact that Zanzeroth happily pauses to give every single excrutiating detail about the supposed crime is reminiscent of the way CSI puts it: that they’re at the scene long after the criminal’s fled and have all the time in the world to piece things together and track him down—which they do NOT. The exposition of the crime reconstruction, interspersed by Gadreel’s grumbling about his lot and of course, the gratituous exposition on how he became a slave—there is simply no sense of tension or immediacy whatsoever. Fail x2.

And what’s up with the numerous titles Bitterwood’s been given? All sorts of crap from “The Ghost Who Kills” to “The Predator” to all sorts of other crap. Also, apparently Mr. Maxey needs to remind us about every 2/3rds of a page that “Bitterwood is no ordinary man”, or some variant thereof. You know, I’m starting to wonder if Bitterwood is an authorial self-insert, but since I haven’t got any evidence to back it up, I’ll give it a pass.

Anyways, Zanzeroth fills one and a half pages with his CSI-style reconstruction of Bodiel’s death, by the end of which my eyes have happily glazed over, thanks to me being utterly bored. La dee da dee da. Anyways, the reconstruction is over, and Zanzeroth happens to slip in the mud. Gadreel goes over to help him up, ad has his offer spurned; the automatic assumption is that the spurning is because he’s a slave. Of course, that ignores the fact that things do happen for multiple reasons; Zanzeroth might have been too proud to accept help from anyone at all, but it’s just a thought on the side. Still, it’s clear that Mr. Maxey can do things right, show events happening and leave it up to the reader to interpret things for themselves. Why he doesn’t do so more often, I have no idea.

In any case, the place retinue of earth-dragons steps out of the foilage (what a convenient place to hide them!) and Zanzeroth has them release the Evil Dogs, a.k.a ox-dogs. Because they’re dogs, and are as big as oxes. Wheeee. The Evil Dogs go sniff about:

“And Bitterwood?” Albekizan said, studing the trees surrounding them. “What became of him?”

“He fled, of course,” said Zanzeroth, placing his spear back in its quiver. “On horseback. He’s miles away but we’ll find him. Even after a hard rain the ox-dogs can follow a horse’s scent.” (Pg. 46)

First things first. Spears do NOT belong in quivers. EPIC FAIL x1. I mean, what the hell? Spear. Does. Not. Go. In. Quiver. Arrows. And. Bolts. Do. And don’t give me that shit. For a spear to be used properly, it has to be a certain proportion of the wielder’s height. Even if these other-people (I really hate calling them dragons. They don’t have the mental, the social, the spiritual, even the physical beyond their own bodies implications of being one) were bigger, the spears would need to be scaled up to their proportions, hence making it impossible for them to practically fit in a quiver. That’s just ignorant and dumb; even CHILDREN know a spear’s too big to fit in a quiver. If they were small enough to do that, you might as well call them “sharpened chopsticks”.

Pant pant

Another question. If the Evil Dogs can follow a scent infallibly, then why the fuck aren’t they tracking Bitterwood directly? Why are they tracking his fucking horse and happily being led on a merry chase? I mean, they have his arrows. Why—oh, I give up trying to get this to make sense. Fail x3. So the hunt is on…and we break the action for one and a half pages of description of earth-dragons, Gadreel angsting over how he became a slave, and yet more angsting on his part. Uh, fine. Whatever. Couldn’t it have been moved to a lull in the bloody action, where there might be a chance to, y’know, at least make getting the information across seem more natural? Besides, I don’t give two shits about Gadreel, and him angsting without me caring first has just tipped the scales against it. PROTIP: get readers to care for your characters before you spill their life story out to them. Fail x4. Anyways, for your convenience and the safety of your brains, I’ve condensed the infodump to the salient points for your benefit:

-Gadreel missed the last three clan gatherings.

-This, apparently, is a serious enough offence for him to be tied up and sold as a slave.

-Zanzeroth won him in a bet.

-Now that he’s in the presence of Evil King almost daily, Gadreel hopes to impress Evil King so much he’s rewarded with freedom.

Oh, look, it’s my old friend the sandvich again. Nom nom nom, om nom. Anyways, the dogs catch onto the horse’s scent, and ta-da! Surprise, surprise, they’ve been tricked! There’s Bitterwood’s horse, but the man himself is nowhere to be seen! DUH! Evil King isn’t too happy about that, and Zanzeroth hands the spears to Gadreel, claiming they’ll only slow him down. Here’s our dear friend’s reaction:

Gadreel struggled to hold the giant wooden shafts with the gleaming steel heads. Only sun-dragons could ever hope to wield such massive weapons effectively. (Pg. 50)

Yeah. Whatever. Right. Which only furthers my wondering at what a fucking quiver is doing holding those things. Anyways, the hunt continues, until they reach a series of cracks in the earth. Apparently these cracks are EVIL and stretch for miles beneath the kingdom, so people (and dragons) don’t usually dare cross them. Cue an infodump on Evil Cracks and speculation as to their purpose and construction, blah blah, four circles being the symbol of death. I really don’t see why. If you look at symbols of death in most cultures, at least most of them have some logic to them. Skulls and bones are very popular in many cultures, as are animals associated with decomposition. Black is popular in western culture. White is the colour of death in Chinese culture, since it represents the paleness of the skin after death. Whatever the case is, there’s usually some logic that ties into the greater part of the culture, with death rites, superstitions and all, but there’s none of that here; it’s just used to explain away why there’s conveniently no one else around and stops there. If you’re going to have symbolic interactionism, at least have a BASIS for it. Minor fail x2.

I’d just like to point out one thing: that on our timescale, man-made buildings do last quite a bit, but on the Earth’s own timescale, what’s probably going to be left of us to the sentient jellyfish or crabs or hippopotamuses is going to be a layer of broken plastic sandwiched between the topsoil and Burgess Shale. I’m already having enough trouble trying to reconcile the use of English, what apparently is magic enough and Evil Advanced Robots without Ruins Of Ancient Civilisation That Was Really Us coming into the picture, thank you very much. The more i read on, the more the setting of this book is starting to look like an issue of Dr. McNinja.

…At least Dr. McNinja has ninja zombie robot pirates ON PURPOSE. Fail x5.

Surprise, surprise. The trail ends at a tunnel, and one of the ox-dogs is dead, having being crushed by a big rock. Now if only more rocks would fall and everyone in this story would be so kind as to die, we could call it a day and go home. Unfortunately that’s not the case, so of course, Evil King just HAS to mention it AGAIN:

“He’s Bitterwood,” said Albekizan. “The predator. He’s no mere human.” (Pg. 52)

Oh god, shut up, shut up, SHUT UP. I don’t want to be told how awesome and fear-inspiring and dark and dangerous your fucking little shit is, really, because—le gasp!—I might actually not agree with the author on how I should feel about this little PoS. The broken record on this topic merely serves to INCREASE my antipathy, not decrease it. Anyways, the chase goes on, and eventually they end up at “an ancient, low building formed of vine-covered brick”. Of course, an arrow comes flying out through a window as they approach, landing right between the eyes of the ox-dog.

Again, I’d like to ask. If Bitterwood had a clear shot at Evil King, and as according to the book blurb, killing Evil King will solve everything, then WHY DIDN’T HE JUST FUCKING SHOOT EVIL KING WHEN HE COULD?

…Oh, wait. Because them we wouldn’t have an excuse to get a 600-odd page book. Silly me. Again, example of idiot plot, where everyone has to be an idiot in order for the plot to proceed. Nom nom nom, om nom. Fail x6. Of course, like the idiot he is, Evil King orders the royal guard into the structure to get Bitterwood out. So they all blindly rush in, and get blown up by a booby trap.

…

…

…Is it really too much to ask for some level of competency in mooks that aren’t supposed to be literally mindless? Is it too much to ask for them to form a perimeter around the structure to prevent Bitterwood from bolting, then send one sacrificial lamb in? It doesn’t have to work, but could they at least try? Pretty please with a cherry on top? Could SOMEONE at least not destroy all tension by having the hero take candy from a baby? Fail x7.

Alas, Bitterwood’s not in the trap, and so we don’t get to see this piece of shit excuse for a Stu get blown up in a ball of flame. Instead, he’s running for what’s recognisable to us as a manhole cover (thank god Mr. Maxey didn’t explicitly call that) and slips inside. Zanzeroth goes after him, just misses catching the bugger, sticks his spear in and a fraction of a second later an arrow comes out of the two-meter-wide hole and grazes his eye.

…

…

…AHAHAHAHAHAAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHA!!!!!!

Ahem.

A very large problem with how bows are represented in today’s literature is how they’re used in the exact same manner as guns are. It’s crept in and embedded itself so deeply into our consciousness that most people don’t flinch when you say to “shoot an arrow”, even though the term is technically wrong. (FYI, it’s “loose an arrow”.) So I’m expected to believe that in that half-second, Bitterwood managed to unsling his longbow (since he was explicitly described as using one, a shortbow wouldn’t have the required kick anyways, and he was using both hands to lift the manhole cover), a weapon that is formally described as at least being as tall as the wielder (wikipedia puts most variants of English longbows at around 6’6”. That’s two meters.) draw an arrow from wherever he’s keeping them, notch the arrow, pull back an arrow about 75 centimeters (about 30 inches) at a power of anywhere from 220 (modern longbows) to 900 (African elephant bows) newtons, and aim it at Zanzeroth’s eye AND loose it.

Mr. Maxey, you’re really fucking stretching the old suspension of disbelief here. EPIC FAIL x2. Now not even the deliciousness of the sandvich can stop me from being a sad dragon now. Really. PROTIP: Even with an M-16 assault rifle fully loaded, you’re not going to go from unsling to fire in a fraction of a second. A pistol, maybe. A longbow? Well, fuck me upside down. Next thing we know, Bitterwood will have the amazing power of bullet time.

After a lot of cursing and swearing, both Evil King and Zanzeroth realise the manhole is too small for them to go into, so Gadreel steps up to the plate and offers to go instead. Hurrah hurrah, thanks for not noticing how those mooks died in a giant fireball. Still, I guess the bravery has to count for something, if stupid recklessness equals bravery.

So Gadreel goes into the manhole, and finds himself in a tunnel “barely eight feet in diameter” and “half-filled with rushing water”. Abandoned sewer, or storm drain? Your call. Most modern storm drains are much smaller than that, though, so it’s definitely an Absurdly Spacious Sewer . A little way into the drain, Gadreel starts having second thoughts, and something catches in his legs. Oh, look, it’s Bitterwood’s cloak. Hurrah hurrah. So our dear Gadreel decides he doesn’t have a spine after all, and goes out with his prize. Evil King isn’t too impressed, but gives Gadreel a figurative pat on the head for trying. We cue back to Zanzeroth, who happens to be toying with the universal panacea in the fantasy genre, also known as “herbs”: